What will become of the sharks?

What will be the future of sharks? These animals that have been around for 450 million years are in danger, threatened by climate change and warming oceans. Now new research published recently in the journal Scientific Reports suggests that baby sharks of the epaulette species are particularly vulnerable, often being born undernourished.

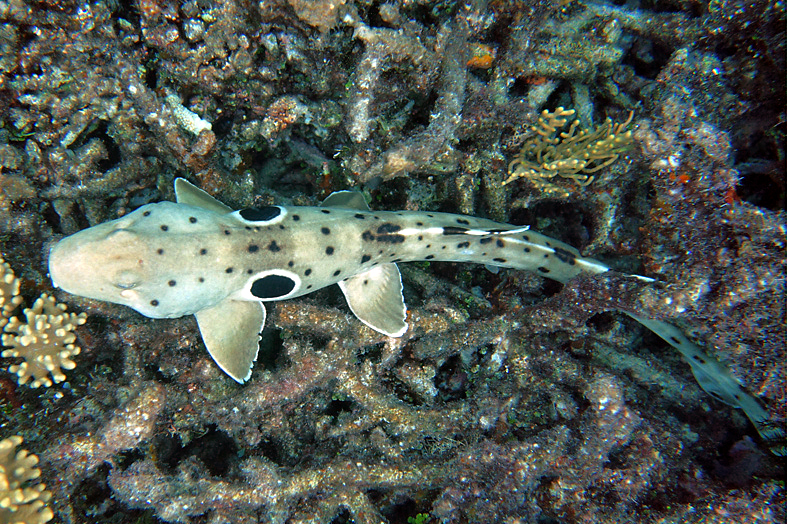

Epaulette sharks are found in the Great Barrer Reef and in the tropical waters off Australia and New Guinea. This egg-laying species became of interest to lead author Carolyn Wheeler, who wanted a model species that could be used to investigate other egg-laying species. Wheeler’s supervisor, Dr. John Mandelman, Vice President and Chief Scientist of the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium, commented:

"The ocean faces increasing threats from humans, such as the effects of climate change, and it is vital to conduct scientific research to help strengthen the management and protection of those ocean species most negatively impacted and vulnerable. In this case, we addressed a pressing threat--ocean warming--and the potential impacts on a species that could serve as a model for other egg-laying species among sharks and their relatives."

Working with the New England Aquarium’s breeding program, Wheeler looked at the impact that warmer water temperatures have on shark embryos. Epaulette sharks have been noted for their abilities to adapt to warming temperatures and ocean acidification, so they provide a baseline from which to measure the potential impact on other, less tolerant species.

"We found that the hotter the conditions, the faster everything happened, which could be a problem for the sharks," said Wheeler. "The embryos grew faster and used their yolk sac quicker, which is their only source of food as they develop in the egg case. This led to them hatching earlier than usual." This resulted in smaller, undernourished hatchlings.

This doesn’t bode well for sharks being hatched in summer water temperatures in the Great Barrier Reef that are anticipated to reach 31°C/87.8°F by the end of the century. Co-author and Associate Professor Jodie Rummer says that these temperatures will put egg-laying species at extreme disadvantages that they may not be able to tolerate.

Sources: Scientific Reports, Eureka Alert