3D Virtual Stimulation Detects Irregular Heartbeats

According to a study published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, researchers at Johns Hopkins University have performed 3D personalized virtual simulations of the heart to assist cardiac specialists in accurately identifying irregular heartbeats. "Cardiac ablation, or the destruction of tissue to stop errant electrical impulses, has been somewhat successful but hampered by a lot of guesswork and variability in the way that physicians figure out which locations to zap with a catheter," says Natalia Trayanova, Ph.D., the Murray B. Sachs Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at The Johns Hopkins University Schools of Engineering and Medicine. "Our new study results suggest we can remove a lot of the guesswork, standardize treatment and decrease the variability in outcomes, so that patients remain free of arrhythmia in the long term," she adds.

For people diagnosed with ventricular tachycardia, an abnormal heart condition, the electrical signals present in the heart's lower chambers will misfire crippling the relaxation and blood refilling process, producing rapid and irregular heart pulses, better known as arrhythmias, and linked to an estimated 300,000 sudden cardiac deaths annually.

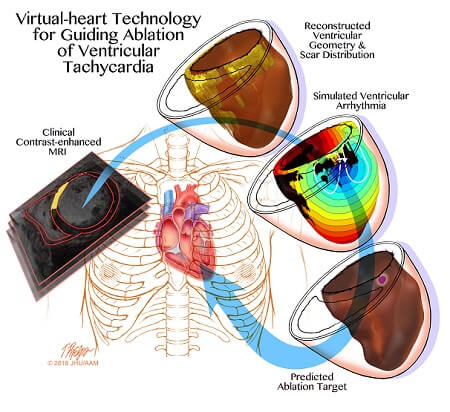

Although numerous drugs are available to treat and manage ‘so-called infarct-related ventricular tachycardia’, side effects and limitations of those drugs have increased focus on other interventions. One such intervention is developing ‘3D personalized computational models of patients' hearts based on contrast-enhanced clinical MRI images’.

In the current research study, Trayanova and research team used MRI images to craft personalized heart models of individuals who previously had successful cardiac ablation procedures for infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. The 3D modeling from these patients have correctly idendtified and predicted the locations where cardiac physicians have ablated heart tissue. The research team then tested the 3D simulation to guide cardiac ablation treatments for patients with ventricular tachycardia. The team demonstrated the legitimacy of integrating a computer-stimulated prediction into the clinical routine. The simulation was created and a prediction was made of where doctors should perform the ablation. The predictions are imported into mapping system before the procedure is performed so that the ablation catheter is transported to the predicted targets.

The research study incorporates personalized simulation predictions for anti-arrhythmia treatment which will reduce the lengthy and invasive cardiac mapping process as well as complications experienced by patients. The technology could also decrease repeated procedures by making the infarcted heart incapable of creating new arrhythmias.

"It's an exciting blend of engineering and medicine," says Trayanova.