There is good news for those suffering with a group of orphan genetic diseases that remain incurable thus far. An international research team, led by Dr. Geneviève Bernard from the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) and Dr. Benoit Coulombe from the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (IRCM), has identified a new gene associated with 4H leukodystrophy, one of the common forms of the disease. Their findings have been published in Nature Communications and reported in Science Daily (http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/07/150708123321.htm).

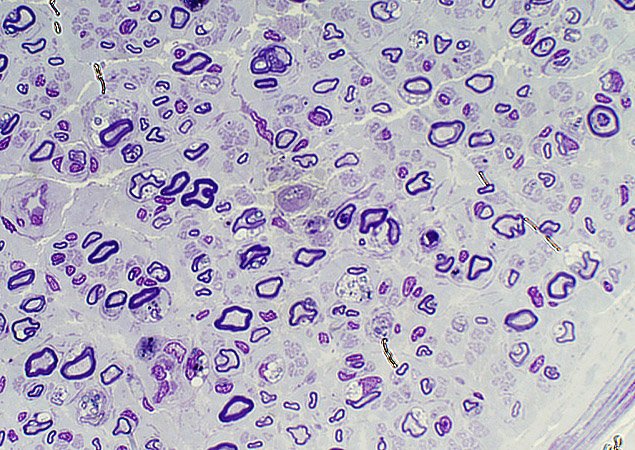

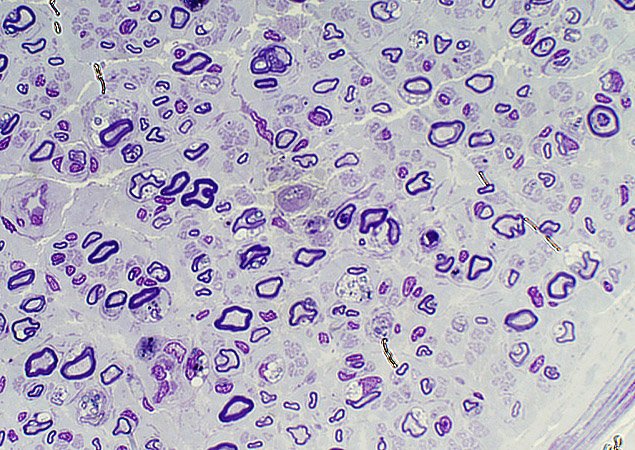

Leukodystrophies, are deadly neurodegenerative diseases that affect one in 7,000 children, attack myelin -- the insulating rubber sheath surrounding neurons -- which leads to deteriorating health for affected children. While 20 types of leukodystrophies have been characterized, others are undefined, leaving nearly 40 per cent of families without a diagnosis.

According to the Leukodystrophies Foundation, leukodystrophies are a group of genetic diseases affecting the myelin of the central nervous system. Myelin, also called "white matter," is made up of a fatty substance whose purpose is to insulate the nerves found in the brain and those that control all the muscles in the body. This insulating layer enables the electric signals to travel correctly through our nerves. Leukodystrophies deteriorate the mechanisms that make it possible to form or maintain this very important protective layer. All leukodystrophies are degenerative, which means that this sheath deteriorates at a rate that differs from one form of the disease to another. That is why the physical condition of children affected by this disease can sometimes deteriorate very quickly (http://www.leukofoundation.com/index-2.html).

As Dr. Bernard, neurologist at the Montreal Children's Hospital of the MUHC (MCH-MUHC) at the Glen site and assistant professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery at McGill University, explains, "We are finally starting to better understand this terrible disease. By discovering mutations on this new gene called POLR1C, which account for nearly 10 per cent of cases with this type of leukodystrophy, we now have a better idea of the impact they have on nervous system cells. My team and I had paved the way in 2011 by identifying two genes (POLR3A and POLR3B) responsible for 4H leukodystrophy, which represent about 85 per cent of patients with the disease. However, approximately 15 per cent of patients with this type of leukodystrophy lack a genetic diagnosis. Until now, we did not know why mutations on the previously-discovered genes caused leukodystrophy."

Dr. Coulombe, full IRCM research professor and director of the Translational Proteomics research unit at the IRCM, adds, "Indeed, we found that mutations on POLR1C caused a problem in the assembly and cellular localization of an enzyme, RNA polymerase III, which plays a very important role in the proper functioning of our cells. The cells' lack of ability to produce RNA polymerase III compromises the genetic program controlled by this enzyme, thereby inducing a particularly harmful effect in specialized nerve cells."

Dr. Coulombe believes that an important step has been taken, both by identifying a new gene causing leukodystrophy and shedding light on the molecular mechanism that enables these gene mutations to be harmful.

Dr. Barnard adds, "Understanding the mechanisms that affect the biogenesis of RNA polymerase III will now guide our efforts in the development of new diagnostic tools to better predict the evolution and severity of the disease, and new therapeutic tools to help sick children. The ability to diagnose this rare and incurable disease has an enormous impact on families, as it helps them better prepare for what lies ahead."